Cognitive aids have been present in the non-medical industry for a long time. For instance, the aviation industry has been using cognitive aids since 1930. The reasoning behind it was that experts in aviation safety considered that even highly experienced and trained pilots may need more than their memory to fly an aircraft safely.

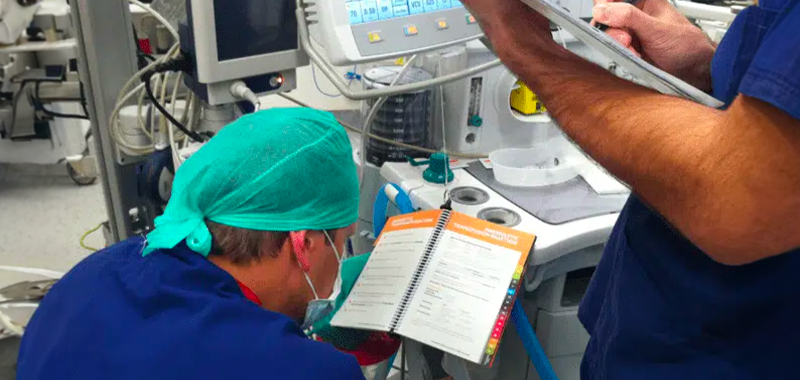

In Medicine, cognitive aids also enhance clinical decision-making and treatment planning, especially during medical crises. Time and resources are limited in a crisis, and even experienced providers may need help retrieving information from long-term memory during high-stress situations. The impact of stressful situations on human memory makes cognitive errors more frequent in the intraoperative setting, especially when the events are uncommon. Cognitive aids can therefore provide a helpful tool to minimise errors.

Unlike protocols or guidelines that describe extensively the state of knowledge and detailed sequences of actions, cognitive aids should be simple and easy to use during emergencies.

Studies on simulation training have shown that surgical teams perform better when crisis manuals are used. Then, many institutions and anaesthesia scientific societies recommend using cognitive aids in the operating room. The SENSAR (Spanish System of Safety Notification in Anesthesiology and Resuscitation) developed the Crisis Manual for Anesthesia and Critical Care. However, there needs to be data about implementing the SENSAR crisis manual. Here, we aim to evaluate the role of the SENSAR crisis manual in the clinical practice of different groups of anesthesiologists.

We conducted an anonymous 5-minute survey. Participants were anesthesiologist consultants from our institution and different institutions in Spain attending a continuing medical education course and residents of anaesthesia from our institution and other regional institutions. The survey completion was understood as consent to participate in the study. This research was conducted by the Helsinki Declaration.

The survey explored the following topics: awareness of cognitive aids in the operating room, usefulness, who should be the appropriate person to read the mental aid, and example of crises when participants used cognitive aids during the last month.

We collected a total of 115 surveys. A high percentage of anesthesiologists and residents -76.5% and 89%, respectively- reported they knew the concept of cognitive aids. However, just one-third were aware of the location of cognitive aids in the operating room. The location and accessibility of cognitive aids are essential factors in enhancing their use. Cognitive aids should be located in a visible, agreed place inside the operating room to be immediately available during the crisis.

To boost the use of cognitive aids, it is also essential that the team perceive them as useful. Most participants agreed that cognitive aids may be helpful in crisis management, even for experienced anesthesiologists. However, 44% of participants were not sure or believed cognitive aids could be a waste of time during crisis resolution. Indeed, if cognitive aids are used at the wrong time, for instance, during cardiac arrest with insufficient clinicians, they could be counterproductive. However, when used at the appropriate time and manner, crisis manuals can be helpful for decision-making and checking for all the necessary steps during a crisis, especially when critical events are not frequent.

Regarding the experience with cognitive aids during the previous month of the survey. Only 12 anesthesiologists (13% of participants) referred to have experienced a critical event during the last month. Cognitive aids were used only in three cases and were helpful in two. Although the number of participants in the survey is limited and the period considered for critical events presentation was probably too short, cognitive aids are far from being used. Only 25% of those facing a crisis used a crisis manual. We consider that active training in cognitive aids is required for their implementation. Simulation scenarios, including cognitive aids, may reinforce their use in actual clinical practice. The mere presence of cognitive aids does not ensure they would be consulted or it would be done correctly. The slight use of crisis manuals in clinical practice has been related to poor knowledge of cognitive aids and the lack of training. Simulation-based training in crisis management, including cognitive aids, is believed to be the most efficacious method. Even previous orientation to mental aid increases the likelihood of its use. The use of cognitive aids has also been reported in the absence of a crisis as a way of training, teaching, or debriefing after a critical event.

There were various opinions regarding who should read the crisis manual during the critical event. Most participants believe that the team leader in a crisis should refrain from reading the cognitive aid themselves. Burden et al. showed that teams that defined the role of a manual reader during a simulated crisis improved their performance during crisis resolution. It would be necessary to study this reader’s role in clinical practice and determine who could assume this role. The usefulness of cognitive aids in crisis management has been widely recognised in simulation settings. The question is whether implementing cognitive aids in clinical practice can change crisis management and whether this change improves patient outcomes.

Written by the Barcelona team

References

- Meilinger PS. When the fortress went down. Airforce Mag. 2004 Oct; 78-82

- Marshall S. The use ofcognitiveaids during emergencies in anaesthesia: a literature review. Anesth Analg. 2013 Nov;117(5):1162-1171

- Driskell JE, Salas E, Johnston J. Does stress lead to a loss of team perspective? Group Dyn. 1999; 3: 291-302

- Staal, MA. Stress, cognition, and human performance: a literature review and conceptual framework. NASA Technical Memorandum. 2004; 212824

- Winters BD, Gurses AP, Lehmann H, Sexton JB, Rampersad CJ, Provonost PJ. Clinical Review: checklists-translating evidence into practice. Crit Care 2009; 13(6): 210

- Clebone A, Burian BK, Watkins SC, Gálvez JA, Lockman JL, Heitmiller ES; Members of the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Quality and Safety Committee (see Acknowledgments). The Development and Implementation of Cognitive Aids for Critical Events in PediatricAnesthesia: The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Critical Events Checklists. Anesth Analg. 2017 Mar; 124(3):900-907

- Hepner DL, et al. Operating Room Crisis Checklists and Emergency Manuals. Anesthesiology. 2017 Aug;127(2): 384-392

- Everett TC, et al. The impact of critical event checklists on medical management and teamwork during simulated crises in a surgical daycare facility. Anaesthesia. 2017 Mar; 72(3):350-358

- Harrison TK, Manser T, Howard SK, Gaba DM. Use of cognitive aids in a simulated anaesthetic crisis. Anesth Analg. 2006 Sep;103(3):551-556

- Krombach JW,Edwards WA,Marks JD, Radke OC. Checklists and Other Cognitive Aids For Emergency And Routine Anesthesia Care-A Survey on the Perception of Anesthesia Providers From a Large Academic US Institution. Anesth Pain Med. 2015 Aug; 22;5(4): e26300

- Goldhaber-Fiebert SN, Howard SK. Implementingemergencymanuals: can cognitive aids help translate best practices for patient care during acute events? Anesth Analg. 2013 Nov; 117(5):1149-1161

- Runciman WB, Kluger MT, Morris RW, Paix AD, Watterson LM, Webb RK. Crisis management during anaesthesia: the development of an anaesthetic crisis management manual. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005 Jun; 14 (3): e1. Available at: https://theacm.com.au/

- Stanford Anesthesia Cognitive Aid Group. Stanford Emergency Manual for perioperative critical events. Available at: http://emergencymanual.stanford.edu/. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- Spanish System of Safety Notification in Anesthesiology and Reanimation. Crisis Manual in Anesthesia and Critical Care. Available at: http://sensar.org/manual-crisis-sensar/

- Marshall SD. Helping experts and expert teams perform under duress: an agenda forcognitiveaid research. Anaesthesia. 2017 Mar; 72(3):289-295.

- Jenkins B. Cognitiveaids: time for a change? Anaesthesia. 2014 Jul;69(7):660-664.

- Neily J, DeRosier JM, Mills PD, Bishop MJ, Weeks WB, Bagian JP. Awareness and use of a cognitive aid for anesthesiology. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007; 33: 502-511

- Wen LY,Howard SK. Value of expert systems, quick reference guides and othercognitive aids. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014 Dec; 27(6):643-648

- Arriaga AF, et al. Simulation-based trial of surgical-crisis checklists. N. Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1368-1375

- St Pierre M, Luetcke B, Strembski D, Schmitt C, Breuer G. The effect of an electroniccognitiveaid on the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction during caesarean section: a prospective randomised simulation study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017 Mar 20;17(1):46

- Nelson K, Shilkofski N, Haggerty J, Vera K, Saliski M, Hunt E. Cognitive aids do not

prompt initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in simulated pediatric cardiopulmonary arrest. Simul Healthc 2007; 2:54

- Gaba DM Perioperativecognitiveaids in anaesthesia: what, who, how, and why bother? Anesth Analg. 2013 Nov;117(5):1033-1036

- Mills PD, DeRosier JM, Neily J, McKnight SD, Weeks WB, Bagian JP. Acognitiveaid for cardiac arrest: you can’t use it if you don’t know about it. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004 Sep;30(9):488-496

- Goldhaber-Fiebert SN, Pollock J, Howard SK, Bereknyei Merrell S. Emergency Manual Uses During Actual Critical Events and Changes in Safety Culture From the Perspective ofAnesthesiaResidents: A Pilot Study. Anesth Analg. 2016 Sep;123(3):641-649

- Harrison TK, Manser T, Howard SK, Gaba DM. Use ofcognitiveaids in a simulated anaesthetic crisis. Anesth Analg. 2006 Sep;103(3):551-556

- McEvoy MD, Smalley JC, Field LC, Furse CM, Rieke H. Use of cognitive aids significantly increases retention of skill for management of cardiac arrest.

- Tannenbaum SI, Cerasoli CP. Do team and individual debriefs enhance performance? A meta-analysis. Hum Factors. 2013 Feb;55(1):231-245

- Burden AR, Carr ZJ, Staman GW, Littman JJ, Torjman MC. Does every code need a “reader?” improvement of rare event management with acognitiveaid “reader” during a simulated emergency: a pilot study. Simul Healthc. 2012 Feb;7(1):1-9